Running Is A Skill

Malcolm Gladwell states in his book ‘Outliers’ that it takes 10,000 hours of purposeful practice to master a skill. If we are spending 10 hours a day sitting verses one hour running, what is our brain mastering?

Running needs to be treated as a skill and therefore the stages of skill acquisition need to be applied. Most people will start in a state of unconscious incompetence, meaning they don’t know how much they don’t know about their running. But it won’t always be like this, eventually with purposeful practice and awareness we can grow to a stage of unconscious competence. This is defined as developing competence to the point where it no longer requires conscious thought for execution.

With this in mind we thought we would start by shining some light on how sitting may be affecting your skill mastery of running, with particular regard to the following;

-importance of hip extension

-how this is affected by sitting?

-what is tone?

-how do we effect tone?

Importance of Hip Extension

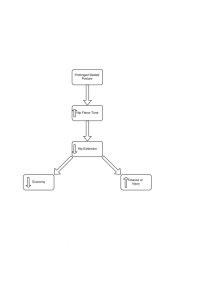

Hip extension is just one piece of the gait puzzle that is running. It is so important for running as this movement aids in propulsion and initiates the knee drive. Electromyography studies(1) have documented that it is this movement that initiates hip flexion, not the hip flexors themselves. This is important for two reasons, injury and economy.

Injury

If inadequate hip flexion occurs there will be a compensation at another part of the body. Do you ever find yourself kicking your toe as you run? If you don’t bring your knee through you might struggle to clear your foot. Your body is a great compensator but this will come at the expense of another part of the body.

To compound this, if you have inadequate hip control this can further detriment your ability to clear the foot during swing phase. This may be noticed in those whose knees may brush each other while running. A compensation which may occur in response to this could be internal rotation of the femur to whip the lower leg out and around to clear the foot. It is important to remember that compensations are not long term solutions. For an awesome insight into compensation mechanisms see David Stroud’s article “Whats in a Goat Track.”

Economy

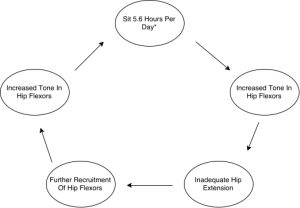

If you cannot adequately extend your hip you will need to call upon another structure to fulfil this duty. This will likely be the hip flexors. The problem is that this isn’t the role of the hip flexors in gait and you are now bleeding energy. It’s like buying energy when you can get it for free. You are using up costly muscular contractions when you could be utilising elastic energy. This is like a Fear Avoidance Cycle, lets call it the Sit Cycle.

Figure 1. The Sit Cycle

Figure 1. The Sit Cycle

How is sitting effecting our hip extension?

Hip extension is predominantly controlled via the gluteal muscle group. However, muscles that oppose one another have a close relationship in the fact that if one is contracting the other will be relaxed. This is what we call reciprocal inhibition.

When we sit all day certain muscles can become tonically short which may prevent us from getting into a hip extension position which therefore can effect our initiation of hip flexion.

Therefore if we have heightened tone in the hip flexors due to prolonged seated postures, the ability for our gluteal muscles to contract will be effected and therefore limit hip extension.

Are my muscles too short?

Are my muscles too short?

Instead of referring to length, let’s refer to tone…

Tone is the continuous and passive partial contraction of the muscles, or the muscle’s resistance to passive stretch during resting state. (3)

Tone will change with demands of the particular muscle. When we sit we may call upon our hip flexors to act as trunk stabilisers, keeping us upright. This becomes a problem as the resting tone of these muscles is then heightened. Sitting is almost being treated as a threat by our central nervous system

How do we affect tone?

A popular misconception is that stretching actually lengthens muscle tissue. Stretching is just a method of altering resting tone just like muscle release techniques, dry needling, or proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation. The problem with this is that unless we do something to consolidate this new found range of motion we will almost always revert back to our previous strategies. Therefore, consolidation of movement via neural priming and stabilization exercises can act as a clearing of the system to negate any perceived threats by the brain. Without this consolidation of movement within the brain we will immediately resort back to what the brain knows…. sitting.

Take home points for those playing at home:

- running is a learned skill

- sitting affects the way our brain controls muscles necessary to run

- we need to provide an alternate stimulus to the brain and then reinforce this message in order to prepare ourselves to run.

Stay tuned because in Part 2 we will look at what you can do to establish good patterns through purposeful practice.

1.(Simonsen E. B. Contributions to the understanding of gait control. Danish Medical Journal. 2014;61(4)B4823)

2. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2013. Sedentary Behaviour. [fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”yes” overflow=”visible”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”][ONLINE] Available at: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/7838D948C8549693CA257BAC0015F644?opendocument. [Accessed 10 May 2016].

3. O’Sullivan, S. B. (2007). Examination of motor function: Motor control and motor learning. In S. B. O’Sullivan, & T. J. Schmitz (Eds), Physical rehabilitation (5th ed.) (pp. 233-234). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: F. A. Davis Company.

[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]